Corruption as a Form of Adaptive Social Resilience in (Not Only) Hungary

A Must-Read for Politicians and "Elites" of Power Structures

What if corruption in Hungary isn’t just a problem — but a survival strategy? This essay reframes corruption not as a moral failure, but as a form of adaptive resilience in response to systemic dysfunction. In a system defined by overregulation, exclusion, and rigid bureaucracy, informality becomes a rational way to get things done. Instead of cracking down harder, maybe it’s time to reform the system that makes informality necessary in the first place.

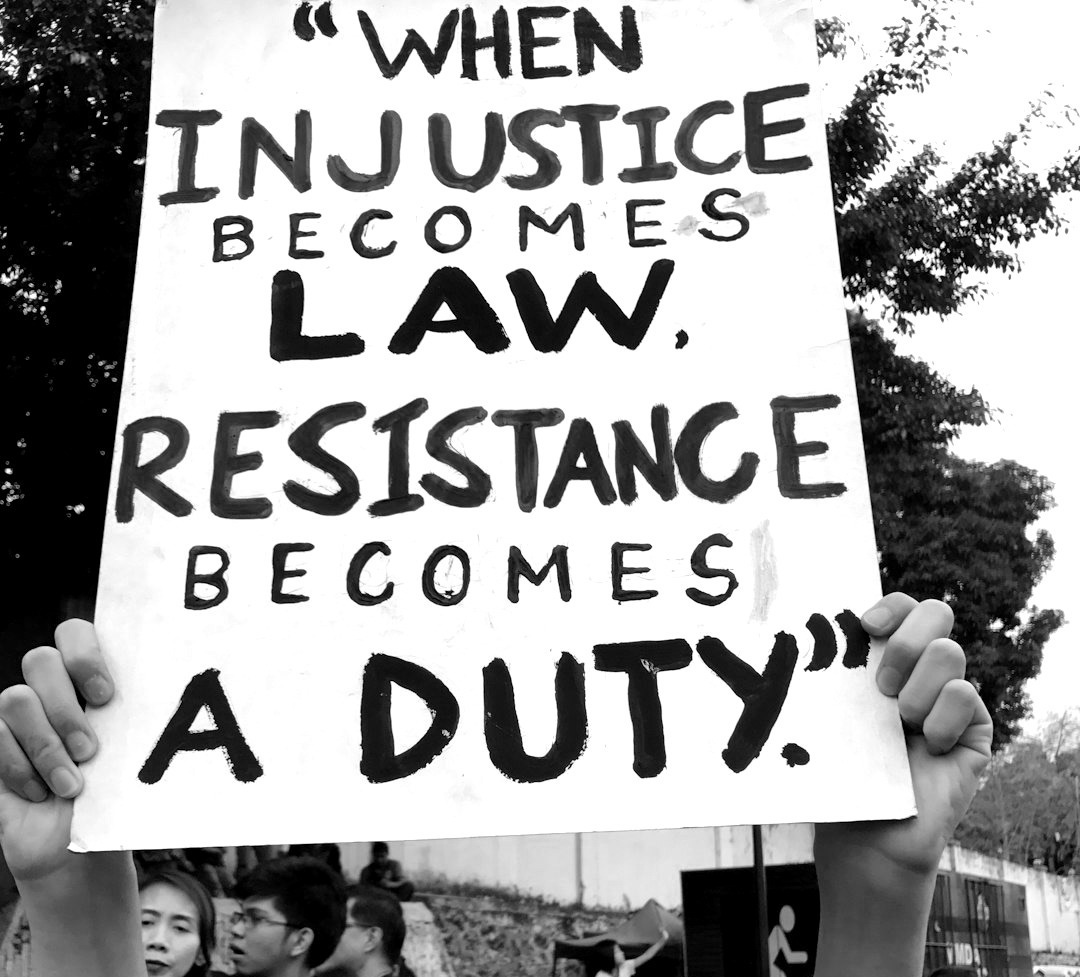

“If nine people say corruption is an unqualified evil, I will be the tenth to ask—what if it isn’t?”

Take 1: Reframing Corruption

Corruption is typically defined as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain. At all levels of society. This may occur in both public and private sectors and often involves bribery, embezzlement, fraud, nepotism, cronyism, or extortion.

Mainstream narratives portray corruption as a purely destructive force: it erodes trust, weakens institutions, distorts markets, and impedes development. This framing dominates international discourse—and for good reason.

But what if this view, while morally comforting, is analytically incomplete?

Take 2: Corruption as a Rational System Response

In my view, within Hungary’s socio-economic ecosystem, corruption functions less as a moral aberration and more as a pragmatic response to deep systemic dysfunctions.

Where legal and economic frameworks fail to deliver equitable access or opportunity, corruption fills the void. It becomes a survival mechanism—an informal workaround in a rigid system that structurally excludes large swathes of society.

Hungary is not unique in this. But unlike many Western democracies where corruption scandals topple governments and delegitimize institutions, Hungary’s elites remain remarkably resilient in the face of repeated corruption allegations.

No major political figure in Hungary has lost power because of corruption.

That fact is not an outlier—it is the system.

Take 3: The CPI is a Subjective Mirror, Not a Microscope

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), published annually by Transparency International (TP), ranks countries based on perceived public sector corruption. Hungary’s steady decline in CPI rankings reflects growing concerns over judicial independence, state capture, and opaque governance.

But the CPI doesn’t measure actual corruption — it measures perceptions of it, mostly among businesspeople and experts. This raises several critical issues:

It captures elite visibility, not grassroots lived reality.

It judges morality, not functionality.

It highlights the corruption of the few — driven by wealth and power accumulation.

It overlooks the corruption of the many — driven by survival needs.

In environments where informal systems function better than formal ones, corruption may not even be perceived negatively — especially by those who rely on it to get by. This isn’t unique to Hungary; similar dynamics exist across several structurally challenged EU economies.

This helps explain why no major political figure in Hungary has lost power due to corruption.

Take 4: Economic Underperformance and Structural Rot

There appears to be a clear correlation between key economic indicators and the warning signs highlighted by the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). According to data published by Transparency International—drawing from the 2024 IMF, 2023 Eurostat, and their own proprietary sources:

Hungary ranks near the bottom among EU member states in both GDP per capita and actual individual consumption.

Romania, long regarded as an economic underperformer, has now overtaken Hungary in household consumption—88% of the EU average compared to Hungary’s 70%.

This is not merely a story of economics—it’s a story of misaligned governance, where the cost of formality has become unaffordable for most.

Take 5: Small Businesses are a Case Study in Informal Necessity

Hungarian SMEs—comprising the majority of the national economy—face a punishing environment:

27% VAT, the highest in the EU.

Pre-financed monthly VAT payments, while clients delay payment for months.

The demise of KATA, which obliterated a tax-friendly regime for micro-entrepreneurs.

Predatory oversight, where small errors lead to massive penalties, and large players enjoy impunity.

In this environment, corruption isn’t about enrichment—it’s about survival. SMEs learn early that success depends more on connections than compliance. And thus, a parallel economy forms, operating by its own informal rules.

Take 6: The Hernando de Soto Theses

Back in the late ’90s, as a political science PhD student, I presented a hypothesis: Hungary’s post-communist transition more closely resembled the Latin American model than other models. Informal networks of former communist power structures took control of most Hungarian state assets during privatization, acquiring them for peanuts, amassing fortunes, and completing the largest transfer of wealth in the country’s history in record time.

At the time, it was dismissed in favor of idealized societal visions inspired by Rawls’s Justice as Fairness—visions that existed only on academic paper. But after decades working in both international corporations and local SMEs, gathering and analyzing market data and insights, I stand by my original view. Like many Latin American economies, Hungary relies heavily on informality to function. This is how post-communist privatization occurred—and, in many ways, it’s still how things work today. I see little evidence that German or U.S. institutional models have truly taken root.

This perspective aligns with the thesis of Hernando de Soto in his influential book The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (2000). De Soto argued that in environments where formal systems are rigid or exclusionary, informality is not a failure of governance, but a rational, adaptive response to systemic dysfunction.

De Soto introduced the concept of “dead capital” — productive assets (like small businesses, homes, or land) that remain outside formal legal frameworks because entering the system is too costly, bureaucratic, or complex. As a result, these assets cannot be used as collateral, traded, or invested productively. They are essentially locked out of the formal economy.

In such contexts, corruption and informality are not aberrations — they are features of survival, engineered by necessity. The problem lies not in the people, but in the system itself.

Take 7: Corruption as Social Resilience

In Hungary, informal exchanges, favoritism, and “gray” transactions are not always viewed with disdain—they are often the only functional pathways to get things done.

A teacher accepts a gift not out of greed, but because wages are insufficient.

A small contractor uses “contacts” to bypass months-long licensing delays.

A startup bypasses official procurement because tenders are stitched up in advance.

These are not stories of villainy. They are stories of functional adaptation—a society building parallel systems where formal ones fail.

This is what we call resilience—though the term is usually reserved for more morally palatable responses.

Take 8: Policy Implications — Fight the System, Not the Symptom

Punishing corruption without addressing the structural reasons people rely on it is like treating fever without curing the infection.

To truly combat corruption in Hungary, policies must move beyond moralism. They must:

Simplify bureaucratic procedures and reduce overregulation.

Ensure fair access to credit, tenders, and state funds.

Level the playing field for SMEs against politically connected giants.

Formalize the informal, giving legal cover and support to existing productive behavior.

Rebuild trust, not just enforce compliance.

Most importantly: corruption in Hungary is not a cultural flaw. It is a governance failure. And failures of governance are fixable.

Conclusion: A System, Not a Scandal

Hungary's persistent corruption is not a story of individual immorality, but one of systemic necessity.

The real scandal is not that people find ways around the system—but that the system demands it.

Understanding corruption as an adaptive survival strategy doesn’t excuse it. It explains it. And from explanation comes the possibility of reform—not just punitive enforcement, but transformation.

If Hungary is to move from survival to prosperity, it must stop fighting corruption as if it were merely a crime—and start dismantling the system that made it necessary.

Disagree? Good. I don’t write to be right—I write to be tested. Bring your “Tenth Man” view, your sharpest counterpoint, or even a quiet doubt. Sometimes the most useful critique is the one that unsettles my own thinking.

Don’t forget to subscribe for more Critical Hungary Insights!